Prostatitis: the prostate problem that can happen at any age

Reviewed by Mike Bohl, MD, MPH, ALM,

Written by Chimene Richa, MD

last updated: Jul 31, 2019

6 min read

Here's what we'll cover

The suffix "-itis" refers to inflammation. Tendonitis is an inflammation of the tendons. Dermatitis is an inflammatory condition of the skin. Prostatitis, then, is an inflammation of the prostate gland, and it's incredibly prevalent. At some point in their lives, at least half of men will be affected by prostatitis. It's estimated that 8% of men visiting the urologist for a urinary tract problem are diagnosed with prostatitis (Collins, 1998).The fact that prostatitis is the 3rd most common problem of the male urinary tract in men over 50 tells us just how common prostate problems are. The top two prostate problems in this age group are prostate cancer and enlarged prostate which is known medically as benign prostatic hyperplasia or BPH (Khan, 2017). It's estimated that in the US, 8% of men visiting the urologist for a urinary tract problem are diagnosed with prostatitis (Collins, 1998). Unlike prostate cancer and BPH, which are seen mainly in older men, prostatitis can affect men of all ages.

Signs and symptoms

Depending on the type, men can have prostatitis with or without symptoms. The most common signs and symptoms of prostatitis are:

Fever/chills

Pain in the lower back or genital area

Needing to urinate more frequently than usual (frequency)

A sudden need to urinate (urgency)

Painful urination (dysuria)

Body aches

Painful ejaculation

A tender prostate on a digital rectal exam (DRE)

Urinary tract infection (UTI)

Classifications

Prostatitis is due to inflammation or infection of the prostate and classified based on the cause and pattern of symptoms. The most widely used classification system for prostatitis is from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes Digestive Kidney Diseases (NIH/NIDDK) (Krieger, 1999). It identifies four categories of prostatitis:

Category I: Acute bacterial prostatitis

Background: As the name suggests, acute bacterial prostatitis is caused by bacteria and develops rapidly. We don't know precisely how many men have acute bacterial prostatitis, but it likely makes up around 10% of all prostatitis cases. It is most common in men 20 to 40 years of age (Coker, 2016).

Symptoms/exam findings: Common symptoms include fevers/chills, body aches, urinary frequency, urgency, and pain with urination. A urinalysis, a laboratory test of the urine, is needed to look for signs of infection. On DRE, the prostate can be enlarged and/or tender.

Causes: Most cases of acute bacterial prostatitis happen because of an infection in the urethra (the tube that carries urine out of the body) that backs up into the prostate causing infection and inflammation. E. coli is the most common bacteria identified in this condition. In sexually active men, common sexually transmitted bacteria, like those that cause gonorrhea and chlamydia, may also be a cause. Acute bacterial prostatitis can also occur after certain prostate procedures, such as a prostate biopsy.

Category II: Chronic bacterial prostatitis (CBP)

Background: While chronic bacterial prostatitis (CBP) is also caused by bacteria, it develops slowly. It typically lasts three months (or longer) with repeated urinalyses showing the same bacteria in the urine, despite antibiotic therapy (Holt, 2016).

Symptoms/exam findings: Common symptoms include pain in the lower back/pelvis, urinary frequency, urgency, and pain with urination or ejaculation. Other symptoms may include sexual dysfunction and mental symptoms, such as anxiety, stress, and depression. Urinalysis shows bacteria in the urine.

Causes: CBP is also thought to start with a urethral infection that then travels to the prostate. Unfortunately, in these cases, the prostate becomes chronically infected with the bacteria; usually, E.coli (Holt, 2016). Men with BPH or sexually transmitted infections are at higher risk for getting CBP.

Category III: Chronic nonbacterial prostatitis or chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS)

Background: CP/CPPS is the most common type of prostatitis and can occur in men at any age. Approximately 90% of men with symptomatic prostatitis suffer from this type. Though it's the most common type of prostatitis, CP/CPPS is also the least understood. Diagnosing someone with this condition entails ruling out other conditions that can have similar symptoms; examples include:

Active urethritis (inflammation of the urethra)

Urinary tract disease or cancer

Urethral narrowing

A neurological disorder that affects the bladder (Krieger, 1999)

Symptoms/exam findings: The symptoms of CP/CPPS can come and go and vary from person to person; they include pelvic pain, pain with ejaculation, and urination problems. The symptoms are similar to those in CBP, but blood and urine testing do not show any evidence of bacterial infection. In addition, sexual dysfunction can be an issue for 40-70% of patients (Magistro, 2016). Men with CP/CPPS complain of premature ejaculation, decreased libido, and erectile dysfunction. Naturally, this can cause a great deal of anxiety and stress, not to mention a reduced frequency of sexual contact (Magistro, 2016)

Causes: CP/CPPS can be inflammatory or non-inflammatory, and often, no specific cause is found. In some cases, a hidden bacterial infection is thought to be the culprit, but tests for bacteria are negative.

Category IV- Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis:

As the name suggests, this type of prostate inflammation does not cause symptoms. Your healthcare provider may find it while looking for other conditions, like sexual dysfunction or infertility. Because men are asymptomatic, treatment is generally not necessary.

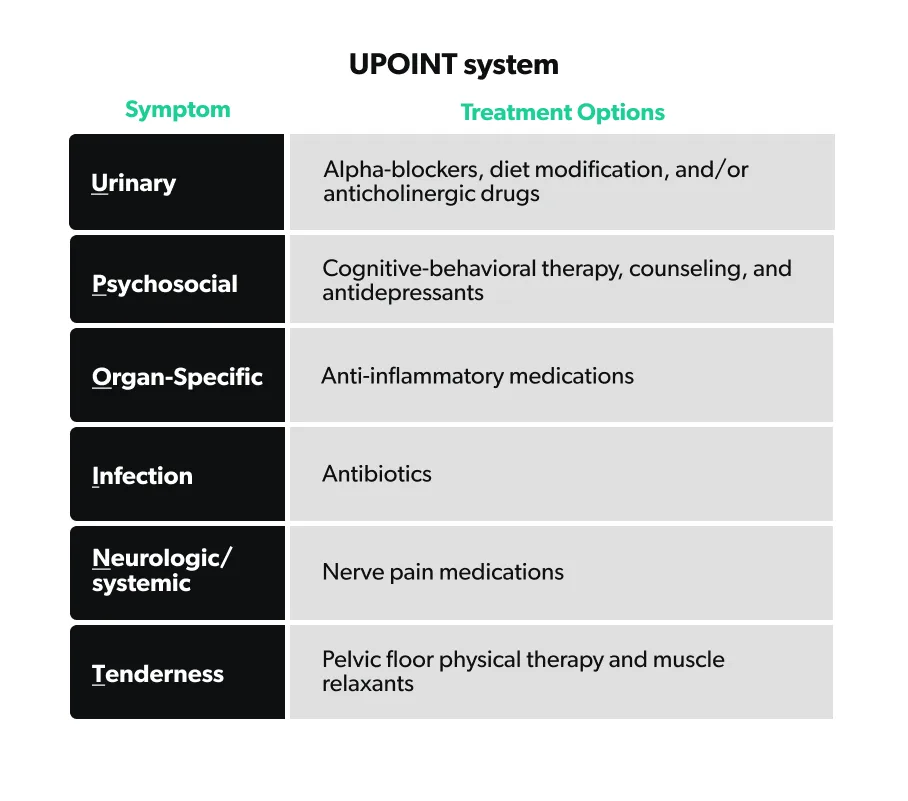

UPOINT symptom classification

Because of the variety of symptoms of CP/CPPS, there is no "one size fits all" treatment. This means that finding the right combination of therapies can be a challenge. Developed recently, UPOINT is a classification system that allows healthcare providers to sort patients with a known diagnosis of CP/CPPS into groups based on their symptoms. The UPOINT system can help guide both the health care provider and the patient down the appropriate CP/CPPS treatment path. UPOINT stands for the following symptom groups (DeWitt-Foy, 2019):

Urinary symptoms: urgency, frequency, nocturia (waking up at night to urinate), and incomplete emptying.

Psychological dysfunction: predominant depressive symptoms, stress, and feelings of helplessness or hopelessness.

Organ-specific symptoms (Prostate and/or bladder): prostate tenderness, white blood cells in prostatic fluid, blood in the semen, prostate calcifications, pain with bladder filling, and prostate tenderness.

Infection: bacterial infection in the prostate, but does not qualify for acute or chronic bacterial prostatitis.

Neurologic/systemic conditions: pain outside of the pelvis that may be associated with other illnesses such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), fibromyalgia, or other chronic pain complaints.

Tenderness of muscles: tenderness and/or spasms of the pelvic floor muscles and muscle trigger points

By using this system, the healthcare provider can target the symptoms that are bothering you the most and improve your quality of life.

Prostate cancer symptoms vs prostatitis

When men, especially older men, have urinary issues like those mentioned above, they often worry about prostate cancer. This is quite understandable given that prostate cancer is the most common non-skin cancer in men in the United States. And while it's true that more advanced prostate cancer can cause lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), it is much more likely that LUTS is associated with a non-cancerous prostate condition, like prostatitis or benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Most prostate cancer is detected during screening of men who have no LUTS. Furthermore, having LUTS does not increase your risk of having or developing prostate cancer. However, if you are experiencing LUTS, you should see your healthcare provider for an evaluation.

Risk factors

What makes a man more likely to get prostatitis? Well, this depends on the form of prostatitis as the different types have different risk factors. Let's first look at the risk factors for acute or chronic bacterial prostatitis (Coker, 2016; Holt, 2016).

Benign prostatic hypertrophy

Urinary tract infections

High-risk sexual behavior

History of sexually transmitted diseases

Urethral stricture (narrowing of the urethra)

History of prostate surgery or procedure

All of the factors above make it more likely to get an infection that can travel to the prostate. In the case of chronic bacterial prostatitis, that infection keeps coming back.

Because the actual causes for (CP/CPPS) are not well understood, the exact risk factors remain unknown. However, it makes sense that patients with a history of surgery or trauma, leading to nerve sensitivity in the prostate, may be more likely to get this condition. Also, psychological stress is thought to play a role (Holt, 2016).

Treatment

As we discussed earlier, prostatitis treatment depends on the cause (if known) and the symptoms experienced. Some of the treatments can be done at home, while others may require prescription medication:

Acute bacterial prostatitis: For most patients, treatment with outpatient antibiotics for 2-4 weeks works well. You should avoid prostatic massage in this situation because there is a higher risk of bacteria entering the bloodstream from the prostate during the massage.

Chronic bacterial prostatitis: Men with CBP need a longer course of antibiotic treatment, usually for 4-6 weeks, but 60-80% of patients will see an improvement in their symptoms (Nickel, 2011). Sometimes over-the-counter pain medication, such as acetaminophen, can help control the pain. If you have issues urinating, your healthcare provider may also add a drug called an alpha-blocker.

CP/CPPS: The treatments vary based on your symptoms, and no single therapy is most effective. However, most men with new-onset CP/CPPS start on a combination of acetaminophen, alpha-blockers, and sometimes a 4-6 week trial of oral antibiotics (Holt, 2016). In addition, using the UPOINT classification system for symptoms can help guide treatment (Magistro, 2016). For instance, someone could have symptoms from group U, P, and T, and the healthcare provider could create an individualized treatment plan.

Management

Medications are not the only option for treating prostatitis. For many men, combining medical treatment with non-medical management of their symptoms can improve their symptoms. Some non-medical management options include:

Warm sitz baths (sitting in 3-4 inches of warm water)

Using a cushion for prolonged sitting

Avoiding food triggers like caffeine or spicy food, if present

Herbal remedies like flower pollen extracts and quercetin (Cai, 2017; Nickel, 2011)

Pelvic floor muscle therapy

Acupuncture, exercise, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation may also benefit some patients

In conclusion...

While there are different types of prostatitis and a variety of treatments, a meaningful conversation with your healthcare provider regarding urinary or sexual symptoms is the first step to getting healthy. He or she will work with you to come up with an individualized treatment plan. Prostatitis can affect a person's quality of life, but you don't have to go through it alone.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Cai, T., Verze, P., LaRocca, R., Anceschi, U., De Nunzio, C., & Mirone, V. (2017). The role of flower pollen extract in managing patients affected by chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a comprehensive analysis of all published clinical trials. BMC Urology , 17 , 32. doi: 10.1186/s12894-017-0223-5. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28431537

Coker, T. J., & Dierfeldt, D. M. (2016). Acute Bacterial Prostatitis: Diagnosis and Management. American Family Physician , 93 (2), 114–120. Retrieved from https://www.aafp.org/afp/2016/0115/p114.html

Collins, M. M., Stafford, R. S., Oleary, M. P., & Barry, M. J. (1998). How Common Is Prostatitis? A National Survey Of Physician Visits. The Journal of Urology , 1224–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63564-X. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9507840

DeWitt-Foy, M. E., Nickel, J. C., & Shoskes, D. A. (2019). Management of Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. European Urology Focus , 5 (1), 2–4. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2018.08.027. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30206001

Holt, J. D., Garrett, W. A., McCurry, T. K., & Teichman, J. M. (2016). Common Questions About Chronic Prostatitis. American Family Physician , 93 (4), 290–296. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26926816

Khan, F. U., Ihsan, A. U., Khan, H. U., Jana, R., Wazir, J., Khongorzul, P., Waqar, M., Zhou, X. (2017). Comprehensive overview of prostatitis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy , 94 , 1064–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.016. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28813783

Krieger, J. N., Nyberg, L., & Nickel, J. C. (1999). NIH Consensus Definition and Classification of Prostatitis. JAMA , 282 (3), 236–237. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.3.236. Retrieved from http://europepmc.org/article/med/10422990

Magistro, G., Wagenlehner, F. M. E., Grabe, M., Weidner, W., Stief, C. G., & Nickel, J. C. (2016). Contemporary Management of Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. European Urology , 69 (2), 286–297. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.08.061. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26411805

Nickel, J. C. (2011). Prostatitis. Canadian Urological Association Journal , 5 (5), 306–315. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.11211. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3202001/